After a long hiatus, I’m excited to resume my writing about travel! As much as I enjoy writing about travel all times of the year, I’ve gotten out of practice due to work, other creative projects and various life events (including having to unexpectedly move), not to mention the fact that I haven’t done much Traveling with a capital “T.” But my husband is teaching a study abroad course in Italy this summer and attending a conference in Dublin beforehand, with me along for the ride. (He noted that he did not even tell me he applied to such a conference until he received his acceptance because, apparently, I tend to get unduly excited about such prospects.) So I currently find myself, for the first time since my spring semester abroad 15 years ago (yes, I am now OLD), preparing to spend a substantial amount of time (two months) abroad. It’s pretty cool, and I feel incredibly lucky that we (barely) have the money and the flexibility to pull it off. But I do have one small worry: that my anticipation, high expectations and tendency to over-plan juuuuust might be my downfall.

Born to Itinerary

The thing is, I am a great planner. I love planning a trip, something I didn’t realize until I planned my first, our honeymoon to Dublin (where we met) in 2016. I was drunk on the freedom of deciding where we would go and what we would do, thrilled by the ability to put together pieces on how we could get to each place and move smoothly from one thing to the next. The truth is, I was probably born to be a travel agent (but not really, because the idea of dealing regularly with airlines makes my palms sweat). But this tendency doesn’t necessary help one enjoy travel; in fact, it can have the opposite effect. While I strive to take a slower pace and avoid the marathon sightseeing of the stereotypical tourist, I have to admit that the kind of planning I do – writing down in a notebook everything I’d like to do, reading restaurant and coffeeshop reviews and the best hive-mind recommendations – is not exactly a recipe for the more romantic and immersive aspects of travel I claim to love.

The Beauty of Being a Know-Nothing

When I think about the experiences that solidified my love of travel, after all, they were not those that I had written beforehand in a mini-notebook or booked through Trip Advisor. During my semester abroad in Dublin, for example, I pretty much knew nothing about anything, bouncing around to whatever bars and clubs that I heard about from my peers (quite a few of them trendy hell-holes), wandering the streets not knowing where or what the historical, cultural or other tourist attraction were, but rather learning as I came across them. (My brother loves to tell the story about visiting me a few weeks into my study abroad experience and having to point out the Spire of Dublin to me, which I had never noticed despite standing right next to it.)

When I returned to Dublin (and I will again this summer), it was with a mind of correcting that behavior a bit, learning more history and culture and trying to go to “good,” “authentic” and “historical” places. Did I see interesting things and eat good food? Yes, of course. But was it more impactful and enriching than the first experience? Absolutely not. Sometimes to really immerse in a culture, you have to try losing yourself, ignoring that pesky controlling voice within. Sometimes, I suppose, you’ve just got to go to some trendy hell-holes to see the light.

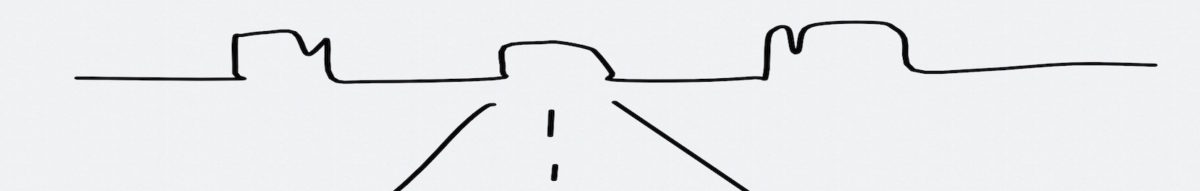

Yet with our two-month European adventure – to Ireland, England, The Netherlands and Italy – just a few days away, I’ve already written way too much in my little notebook (and the impulse remains to write more). The travel agent in my head wonders if it isn’t a good idea to look up a few more London restaurant recommendations, to pour over my Dublin map and find out what route I might take on a meander (yes, I’d still prefer to call it that) through the city. You really should review a map of Venice, it says, despite the fact that I’m not even going there until July, and I’ll have my laptop and phone with me the entire trip.

Thus, I’m attempting to push that little travel agent within aside. Instead of building my anticipation and sheer delight at the thought of the summer ahead (and that delight is a big reason travel planning is such an addiction), I’ve decided to turn my attention to why I really enjoy travel. I’ve written in the past about things I like to do when traveling, the places I love, and why travel is important, but in my cloud of precision-planning, I don’t want to lose my own reasons for travel, its mental and emotional impact.

Focusing on the Why

So, why is it that I like to travel? This may seem like a strange question, as generally in our society long-distance travel, even for work, is something about which we’re expected to be excited. When I happen to share the news that I’m embarking upon a two-month trip to Europe, the standard responses include “That’s so exciting!” “You must be so excited!” “I’m jealous!” etc., etc. I’m sure that, in part, this has to do with my tone and countenance; if I sighed heavily and explained that I *had* to travel all summer because my husband was dragging me all sorts of places, perhaps they’d react differently. (Though they’d probably think I was at best odd and at worst a potentially miserable person.) But what is it about going somewhere with a different culture (even one that’s only slightly different in the grand scheme of things) that feels so thrilling?

Lost and Found

There are many schools of thought on travel, and it’s honestly a subject that’s been written to death by backpacker types on every blog and website imaginable (insert photo here of girl in anorak standing on edge of mountain). Two perspectives seem to come up again and again: 1) that travel helps you find yourself and 2) that it helps you lose yourself. I’ve personally vacillated between these. I think of the times, when I was a kind simple traveling to my grandparents’ house in eastern Pennsylvania from Illinois, how I felt blissful at the opportunity to be away from home, and how it stoked my imagination with dreams of being somebody different. I think of the delight I feel still in being anonymous on a foreign city street, in a market, on a bus or train, willing myself to fall into a new city’s complex choreography. These sensations fit pretty snugly in category two.

But I also think of the more enriching moments of travel, the negotiations and interactions, the attempts to explain myself and to find out about others. I think of the things I’ve seen and the things I’ve learned, and how I must wedge them into my formed conception of the world, how I’ve turned them over in my mind and processed them through my experiences. I think of the experience of a semester abroad, and how what at first felt disappointing and disorienting became a time of personal evolution, of coming of age and developing a sense of myself.

It’s this last thing that really gets to the heart of it. The fact is, travel can be about both losing yourself and finding yourself. If I really dig deep to suss out the appeal of travel, to me, is the way it combines a feeling of hyperawareness of oneself with a sort of forced reset. Thrust yourself into a foreign country, with all its attendant communication issues and challenges, and you’re forced to confront the person you truly are: how you relate to others, how you respond to challenges, what aspects of culture you are drawn to, which ones you misunderstand or fear. You are removed from the familiar surroundings that sometimes obscure these aspects of your identity, and thus they come into sharp relief.

But you lose yourself in some ways, too. Trying to forge relationships with those from other cultures can be challenging; because you lack a cultural shorthand and perhaps also have a language barrier, it can be difficult to show them who you really are. It can be frustrating to compare these encounters to those with friends at home, and wish the people you met abroad could know you in that same way. But isn’t it thrilling to be someone ever-so-slightly different, to figure out how to present yourself in a new context? To navigate new situations like this can make us feel foolish and uninteresting (in Italian my conversation is basically limited to asking a person how they are, and then naming different types of food, clothing and animals) but it also shakes you out of complacency, and forces you to answer for your beliefs and attitude in ways you never have before.

Coping Mechanisms for Losing Yourself

When I’ve led study abroad classes in the past, I’ve at times had to check my frustration when students become absorbed in Instagram during sightseeing expeditions, meals or meetings, or when they ignore the tour guide’s insights in favor of discussions about the minutiae of life back home. Think about where you are! I want to remind them. You may not be here again! And yet, I also realize that these behaviors are not a sign of apathy or disinterest per se: they are in fact a natural response to the unmooring sensation of travel. The students are out of their cultural context – many for the first time – and it can feel alien and dangerous; not only in the sense of physical, walking-down-an-unfamiliar-street-at-night danger, but in the sense of losing the context within which we feel defined and unique. Some of us turn to social media and to banal discussions of fraternity parties to continue to grasp a firm identity, to make sure we still understand ourselves.

And some of us, we plan.

It’s a natural reaction and, whether or not you give in, travel will change you.

I know that this summer will not be as life-changing as a first trip abroad, but I also know that if I let go a little, these two months will have something to teach me. Here’s hoping I can stay committed to write a bit about the amazing places I will visit. Stay tuned!