Small Towns in Decline

I have a fascination with forgotten places, particularly faded small towns. I’m not referring to ghost towns, which are much more rare. Faded small towns that still have people and life and schools and community and businesses, but they’re towns that once were something bigger and more prosperous, and they must wear their decline on their sleeves. They’re towns for which vacancy is a fact of daily life.

One thing I learned growing up in a larger version of one of these towns is that it costs more to demolish something than to let it sit empty. So all around my hometown of Galesburg, IL (which is currently doing okay but, like many towns of its size, declined in the latter half of the twentieth century and was walloped by factory closings in the ’80s and ’90s) there are empty buildings, shuttered and dusty. Some have stood, silently the same, since my early childhood. Their hopes seem to dim just a tiny bit each year, like they’re still awaiting the return of long-gone inhabitants.

Small towns all over the United States are currently in decline due to a number of factors: a loss of manufacturing jobs due to outsourcing and automation, a generational shift away from small communities and toward more urban areas, and the fact that national corporations and online retailers have taken the place once held by local mom-and-pop shops. I’m not here to romanticize the very real economic hard times that small towns face, but I do like to look for the beauty in these forgotten places. Empty storefronts and neighborhoods tell us about a town’s past and the people that have lived there. And the parts of the community that remain vital tell us about what the town is becoming, and how it reconciles the past and the future.

Green River, Utah

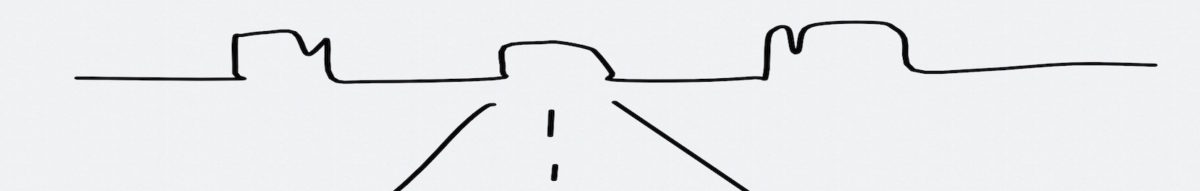

Our drive from Canyonlands National Park to Cedar City, Utah was one of the most beautiful – perhaps the most beautiful – I’ve ever taken. Each mile seems to bring more unusual redrock formations: spires, canyons, and mesas. It’s totally desolate, with no services for miles but a number of scenic viewpoints, an acknowledgement that sometimes you’ve just gotta pull off and take it all in. There are few towns along this route, but for lunch we chose Green River, Utah as our stop. And I’m glad we did.

Green River is a prime example of one of those forgotten places that I’ve always found so intriguing. According to the town’s Wikipedia page, Green River was one of the pass-through areas of the Old Spanish Trail trade route in the mid-1800s. In 1876, it became a river crossing for U.S. mail and evolved into a popular stop for travelers. A railroad boom helped grow the town until 1892, when operations moved elsewhere. But the second boom in Green River – the one we see remnants of today – came in the mid-twentieth century, when uranium mining brought more prosperity to the town. In the 1960s, an Air Force missile launch facility was also established, and the population reached its peak during that decade. But once the mining industry dried up, the population dropped to around 900, where it sits today.

Currently, most of the town’s economy mostly rests on the shoulders of I-70, as it caters to travelers and truckers, as well as mountain bikers (the town is a popular freeride spot). There’s also a natural gas field nearby. The town is quiet but friendly, and by necessity welcoming to outsiders.

Storefront Poetry

Downtown Green River has a large number of empty businesses, sprinkled casually between a few still-open restaurants and shops. Many of these are fairly well-preserved, with old signage still intact, offering a nice little slice of the past. The most inspiring thing I saw during my short visit to Green River was a poem someone had written in the window of an abandoned storefront. Composed by an unknown author, it reads:

Sitting on the river’s edge

The smell of driftwoo

(Not exactly driftwood; drift sticks

washed ashore from a recent

rain & subsequent flood).

Muddy water.

Sun sets behind the butte

Slowly, like when you sit [cut off]

bathtub and let [cut off]

drain, lying still, [cut off]

In small pulses as it drains

Pulling you down, increasing

gravity, pulling away the weight

of sadness, getting chilly but

also still warm on the bottom

half of you, if split longways.

It’s a small, personal poem. Maybe not a masterpiece, but way more moving than something I expected to read on the papered-over window of a shuttered business.

The Place for Everyone

I can only imagine there are many other such instances of subtle beauty in Green River, one of Utah’s forgotten places. Though I only spent about an hour there, I sensed something special in this town.

We spent most of our time in Green River at Ray’s Tavern (slogan: “the place for everyone”), one of a few local eateries, with a charmingly brief menu featuring burgers and fries, beer and wine (a selection of various Franzias, naturally), steaks, chops, and apple pie.

After devouring our burgers, it was time for us to hit the highway. But Green River and its mysterious faded charm remained on my mind. It’s one of the many small towns in this great big country that seems easy to ignore, but deserves a second look.