“a strange world of colossal shafts and buttes of rock, magnificently sculptored, standing isolated and aloof, dark, weird, lonely.”

– Author Zane Grey on Monument Valley

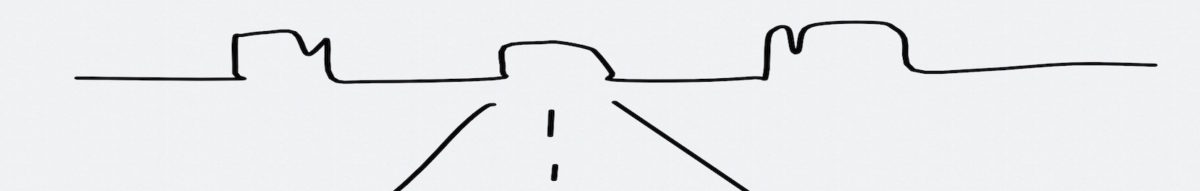

It’s been over a month since I returned from my road trip around Utah, but I wanted to take my time gathering my thoughts about Monument Valley, a famous park situated on Navajo land at the Arizona-Utah border. Monument Valley is a breathtaking place that invites a strange sensation: it’s totally unique and yet instantly familiar, even if you’ve never heard of it before in your life.

Visions of the American West

In my first post about our Utah trip, I wrote a little about the mythos of the American West, the way it exists in the minds of those of us who have yet to experience it in person. When I talk to friends, especially those from other countries, about where they most want to visit in the U.S., they usually want to go somewhere out west based on this mythos, what they’ve seen and heard and read in popular culture. As I took in the sites of Arches National Park alongside a number of tourists from Europe and Asia, I wondered if what they saw matched their expectations. but I realized that in this globalized society, we probably all have similar points of reference. So to understand what was in their imaginations, I needed to look no further than my own.

Monument Valley in Pop Culture

Though we may not realize it, when many of us picture the American West, we picture Monument Valley. I know I did, for the simple reason that it is far away the most frequently-filmed western location, appearing in countless films and television shows, beginning with John Ford’s 1939 John Wayne film Stagecoach (Vanity Fair published this excellent article some years ago on Ford and Monument Valley). Monument Valley’s pop culture path was forged by Harry Goulding, a rancher who moved with his wife to the barren valley in the 1920s and established a small trading post. When Goulding heard that United Artists was scouting locations to film westerns, he hired a photographer to put together an album, made his pitch, and the rest was history.

After Stagecoach, John Ford continued shooting movies at Monument Valley, returning again and again to the iconic landscape, and other filmmakers followed suit (and continue to do so to this day). Films featuring the Valley include 2001: A Space Odyssey, Once Upon a Time in the West, Easy Rider, National Lampoon’s Vacation, Thelma and Louise, Forrest Gump, and many more. But I have to attribute my mental image of Monument Valley to a decidedly less highbrow source: Looney Tunes. During the cartoon’s heyday in the 1960s, animators Maurice Noble and Chuck Jones – likely inspired by the western films that were popular in their youth – used Monument Valley as the setting for many shorts, most frequently the Wile E. Coyote and Road Runner cartoons.

It’s fascinating to consider how our expectations and conceptions of any particular place are colored by these sorts of tangled associations: my personal understanding of the American West started with Looney Tunes, which in turn was likely drawing from the early impact Western films had on the animators themselves. No matter how it got lodged in our minds, Monument Valley has become shorthand for “American West” for generations of people – not bad for a relatively small swath of land smack-dab in the middle of nowhere.

A Visit to the Valley

But I suppose that’s enough pontificating for now. What travelers should know is that Monument Valley is an incredible place to visit. It’s remote but situated near enough to Bears Ears, Grand Staircase, and even the Grand Canyon that it makes an excellent stop on a multi-park tour. One point to note: the park is on Navajo land and thus is officially a Navajo Tribal Park, not a national or state park. This doesn’t make much of a difference in terms of amenities, but it does mean there are more interesting culture facets to the experience – a Navajo museum within the Visitor’s center includes historical artifacts and art, and the two on-site restaurants both specialize in Navajo food. And it also means that there’s very little else nearby, which makes the experience more special, in my opinion.

We stayed at Goulding’s Lodge, the cheaper of the two lodging options in the park (the other being the View Hotel, which has better views but a less charming decor). Goulding’s is on the fancier side of what I consider a “lodge,” and one of my favorite things about it was their amazing logo. Though I snagged some of the above notepaper, I was sad to discover this logo is not available on a t-shirt.

The Goulding’s dining room serves a typical diner menu with the addition of some Navajo dishes. Figuring I’d be a fool not to eat Navajo food while I had the chance, I ordered the Navajo fry bread huevos. The portion was uncomfortably massive, but I didn’t regret it. Later on, we tried the View Hotel restaurant for dinner, and I had a pretty good green chile stew. The View’s selling point is – you guessed it – dinner with an exceptional view of the monuments. But to get a window seat for sunset, it’s best to show up when they open at 5:00.

Monument Valley is different from many National and State Parks in the area in that there is only one hiking trail – this is really a driving park, whether you choose to do so in your own vehicle or sign up for a tour. We chose to combine our visit with a drive to Valley of the Gods, so we didn’t take the standard Monument-viewing drive. Though it was quite cold, we decided to take the full hike, which lasts a few hours and only features one truly difficult patch (walking up a steep hill in sand – something I’d never done before and wouldn’t necessarily like to repeat). We were the only two people out there on this particular cold Saturday afternoon, and the hike was nothing short of glorious – like being on the moon.

There’s also a lot of kitsch to be experienced at Monument Valley. Harry Goulding’s old trading post and apartment is now a museum featuring film posters, Navajo art, and other artifacts from the Valley’s history. Goulding’s Lodge also has a screening room, naturally, where John Wayne films typically show, in case you want to pop in and see depicted on celluloid the very landscape that surrounds you. There are two massive gift shops as well with a wide variety of must-have junk. But due to the austerity of the surrounding area, none of this feels like too much, and it’s easy to ignore if you prefer a more nature-centric experience.

For my money, the biggest thrill of all was just waking up in the morning, glancing out the window of the lodge (camping would be amazing, if you come in warm weather), and seeing the sun rise over those mighty, wild towers of rock. It’s a vision that perhaps your mind already has stored, from Elmer Fudd chasing Bugs Bunny or John Wayne searching for Natalie Wood or Chevy Chase wandering, delirious, in Vacation. But to see it in person, to stand in the midst of it – you can then truly understand what Harry Goulding saw all those years ago. That this is one of the more special places in the world, and that it needs to be shared.