Last Friday, February 2nd, was a sad day for proponents of public lands: areas that were formerly part of Bears Ears National Monument officially opened for mineral leasing. This means that oil, gas, coal and uranium companies can now put in requests to mine these beautiful parts of Utah. Why? The usual – money, politics and shortsightedness. So how did we get here? For those who haven’t followed the story, in December President Trump issued an executive order shrinking Bears Ears (along with Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument) – which was designated by President Obama in just 2016 – by 85 percent. What remains are two protected areas, newly christened Shash Jaa and Indian Creek, and among the rest there is some local protection, but mostly none.

This January, I visited the Valley of the Gods, a breathtaking valley of sandstone formations that is considered sacred to the Navajo. It is one of the areas that the executive order removed from National Monument protection. We went other places on our Utah adventure before we made it to Valley of the Gods – including Zion National Park and Monument Valley, which I’ll post about eventually. But the recent news of mineral leasing compels me to share my brief, memorable morning in the former Bears Ears, in words and photos.

I have to note one thing up front, and that is that Valley of the Gods specifically is still protected public land under the Utah BLM. It is a designated Area of Critical Environmental Concern, which I believe means there won’t be any mining or drilling on this particular spot. But this is just one small section of an area that is rich throughout in beauty, history, and archaeology. And some arbitrary parts of it are now free to be corrupted, disrupted, and exploited.

Throughout the debate over Bears Ears, some have asked: why the uproar over the reduction of the monument when it’s only been around for a little over a year? It was doing just fine before, wasn’t it? But the answer is no, it wasn’t.

For years, this expanse of land was subject to vandalism, looting of valuable artifacts, and even grave-robbing. It was this dire situation that prompted a coalition of Native American leaders to petition president Obama to designate the monument. As Jenny Rowland wrote in 2016 for the Center for American Progress, “The combination of Bears Ears’ vast size, number of archaeological sites, surge in looting incidences, and unprotected status make it the most vulnerable place in the United States for these kinds of activities.” Securing its protection was a great step forward in the preservation of Native American history as well as nature. But unfortunately, we’ve now taken a step back.

Exploring the Valley

Valley of the Gods is located near the town of Mexican Hat, just a 30-minute drive from Monument Valley, so it is one of the most accessible parts of the former Bears Ears. Reading about this area, we didn’t get a full picture of just how desolate and interesting it was, however. Once we drove out, it was clear we were in the honest-to-God middle of nowhere. In fact, the whole surrounding area, which is Navajo country, felt unique to me in its quiet – there are not a lot of towns and very few amenities, particularly in the off-season. It was just us, the land and the sky, and the occasional “rez dog” on the side of the road.

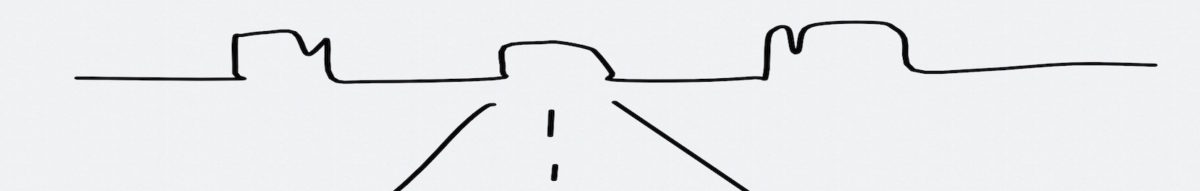

I was a bit concerned about exploring Valley of the Gods at first, because it’s only traversable by a rocky dirt road, and we were driving a 13-year-old Volvo sedan. But it was a dry day, so it turned out to be fine, if quite bumpy. Word of warning to those setting out – pay attention to the conditions. If this road gets muddy at all, you’re likely to get stuck. There are other amazing things to see in the area if you’re wiling to traverse the white-knuckle drive up the mesa called the Moki Dugway. Despite my husband’s attempts to convince me, I felt better keeping our little car on reasonably level terrain.

A Truly Alien Landscape

The formations throughout Valley of the Gods are both like and unlike anything else I’d seen in Utah. While the overall red rock and desert-like conditions were similar to what we’d seen at Monument Valley and Zion, the delicacy in the way the rocks seem to have been carved was something new. The name “Valley of the Gods” does it justice – it’s like some divine version of Mount Rushmore, with iconic and commanding figures staring down from a cloudy sky.

To invoke another strange visual comparison, our drive through Valley of the Gods also felt to me like a trip through the Disneyland Upside-Down. One minute we would encounter a bank of castle-like formations, the next a great craggy shipwreck, and later a field of alien pyramids. It was empty except for one or two passing cars, and at times we felt like explorers on another planet.

The “Why” of It All

The whole time, of course, we were asking ourselves one question: how could someone look at these lands, like a slice of Mars here on earth, and decide that they had been granted too much protection? That guaranteeing their longevity and accessibility to the public is a bad idea? That possible mining and development – or that thorny issue of states’ rights – could possibly take precedence over preserving the sheer wonder (not to mention historical value) of this place?

I’m glad to know that for now, the Valley of the Gods is somewhat protected by the Utah BLM. But Trump’s executive order regarding Bears Ears sets a dangerous precedent – that conservation is okay until we decide we want something else, namely money. And then these areas, so rich in history and majesty, are at risk of becoming as expendable as those in power want them to be.